Why Doesn’t Success Feel Like Enough?

Field Notes exists to honor the unseen — the scaffolding of creativity, community, and change.

Hey, I’m Lindsey. Nearly 500 of you are here now, and more than 25 of you have already backed this project with your own money — holy shit. I’ve gotten a bunch of messages asking how I got here, why now, why Field Notes. So, here’s my answer.

We celebrate the album drop, not the van breaking down at 3 a.m.

We cheer the skyscraper, not the hands pouring concrete before sunrise.

We frame the wedding photo, not the hours of unseen work that made that moment possible (for the photographer and the couple).

That’s the problem. We’re obsessed with outcomes, and blind to what actually holds.

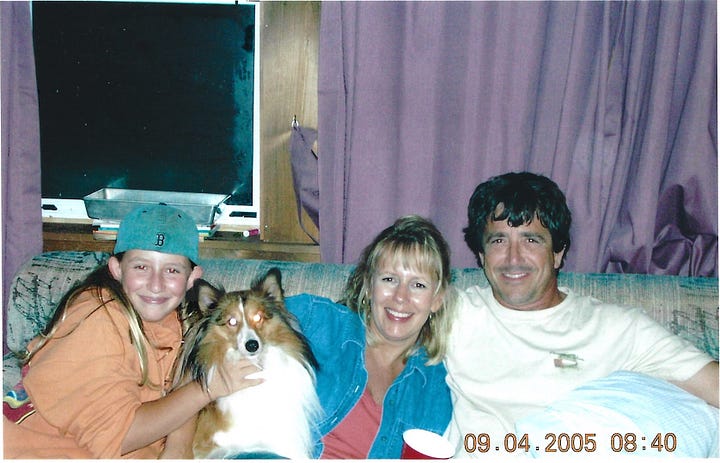

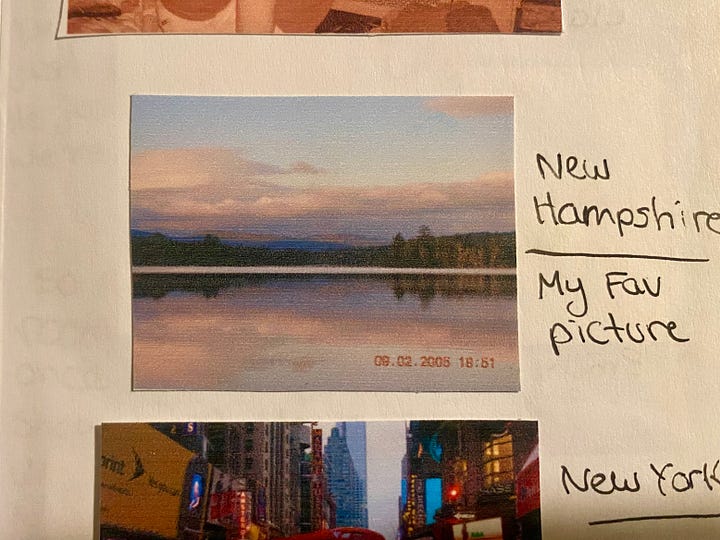

I’ve known this since I was a kid. I always had a camera in my hands. My first point-and-shoot was a Nikon from Best Buy. The first trip I took it on was to New Hampshire. I was already noticing — the light on the lake in Littleton, the way people shifted when they thought nobody was paying attention.

The camera opened doors I couldn’t walk through on my own. I was introverted, anxious, but with a camera in my hand, no one questioned me.

And people liked my photos. They told me I had an eye. But the first time anyone got excited was when I started making money — shooting weddings, bar mitzvahs, portraits. The irony is, I was just as good before the checks came in. The only thing that changed was money.

And that’s the fracture we’re all still standing on. We don’t value the unseen until it can be sold. We don’t trust care, creativity, or noticing unless there’s a price tag attached. That’s not an accident — it’s the inheritance of business itself.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the word business comes from Old English bisig — meaning “anxiety, occupation, busyness.” Business literally meant anxiety. And we decided to build an entire culture around it. Which is fucking wild when you think about it.

Then came the Industrial Revolution. Machines started taking over the repetitive, backbreaking tasks people hated. That could have been the moment we carved out more room for creativity, for care, for connection. But no. We doubled down. We didn’t ask what we could imagine once machines took over the mills and the mines. We asked how to crank it faster, make it cheaper, squeeze more out of the same 24 hours.

That’s the inheritance we’re living with: productivity as morality and output as identity. You’re only as good as your numbers. How many hours billed? How many products shipped? How many emails answered before midnight?

And when you grow up inside that inheritance, you learn fast that your art — your creativity, your noticing — doesn’t “count” unless it produces. Unless it sells. That’s how a kid with a camera, who was perfectly fine noticing the light on a lake, ends up cosplaying as a businessperson.

Because society will applaud your hustle long before it will honor your art.

Eighth grade is when the slide started. I was in the school band. A few of us wanted to play a popular song at the show instead of the piece our teacher picked. Nobody knew how to make it happen. My anxiety couldn’t handle the chaos, so I jumped in.

I found the chart. Split the parts. Booked the extra practice. Chased people to actually show up. Talked our way onto the program. The song landed. Everyone clapped.

That was the crack. The moment my creativity got traded for coordination.

First it was the band. Then the tour. Then the whole damn business.

It felt good at first. Recognition is a hell of a drug. My photos got compliments, sure, but being trusted to keep the wheels on? That was attention I could measure. People needed me. They handed me the keys. When you’re a kid desperate to be seen, being indispensable feels like proof you matter.

But the trade crept in. Every yes to logistics was a no to the mess of making. The better I got at holding it together, the further I drifted from the reason I was there in the first place. The role hardened. I wasn’t the artist; I was the organizer.

That pattern isn’t random. It’s historical. For centuries, women have been tasked with the invisible work — caregiving, coordinating, smoothing the edges so life can happen. When industrialization pulled men into factories, women absorbed the rest — childcare, housework, elder care — unpaid, expected, unseen. That inheritance didn’t disappear. It just changed outfits.

On tour I was “manager,” but most nights I was the babysitter and the back-of-house therapist. I made sure people ate. I made sure no one spun out. I made sure the show looked effortless from the outside.

And yes, I was good at it. Being good doesn’t make it yours. I wanted to be valued for my creativity. What I got was recognition for execution.

By the time I started my first company, Level Exchange, I had fully bought into the lie: if I wanted art to be valued, I had to prove it was a business. Art was a business and business was an art. We even stamped it on t-shirts and put it in the pitch deck — growing art into business. I thought if I could show the numbers, if I could package the whole messy beauty of music into something fundable, then maybe people would finally care.

And they did. Investors perked up. City officials nodded along. People finally started paying attention. I was being recognized.

Unfortunately, recognition is not the same as understanding.

What I wanted was to be valued for my creativity — for the vision, the spark, the thing behind the thing. What I got was applause for my ability to get shit done, again.

And every round of applause felt more hollow. Because while everyone else saw a founder with traction, I felt myself slipping further and further away from the artist I had been. The kid with a camera. The drummer. The one who noticed things. That part of me was dissolving under spreadsheets and pitch decks.

That’s the cruelest part. I was creating startups and enterprises in a creative way. They didn’t look like what people expected, because they weren’t built inside the usual frame. And the usual frame — patriarchal, colonial, utilitarian — is designed to reject anything that doesn’t serve profit first. There’s no room in those systems for approaches that make space for care, creativity, or alternative ways of building.

So the ideas didn’t stick. And I was left frustrated, deflated, and fucked up.

But this isn’t just my story. It’s a cultural pattern. For centuries, creativity has only been protected when it could be justified in economic terms. In the 1930s, artists got WPA funding only if their work could be framed as “public infrastructure.” In the decades since, NEA budgets have been gutted again and again because art that doesn’t generate measurable “value” is seen as frivolous. Even today, school districts slash arts programs first while doubling down on testing.

Level Exchange was my local-scale version of that same trap: look, I can prove art is valuable, because it makes money. But the more I played that game, the more I lost myself.

That’s the cost. When we force art to prove its value through enterprise, we strip it of the very thing that makes it valuable, its humanity.

Collapse doesn’t start at the breaking point. It starts in the places no one bothers to look. The scaffolding ignored until it cracks. The invisible labor written off until it vanishes. The care taken for granted until there’s nothing left to give.

That’s where I found myself. I had built my way out of being an artist. I was the manager. The fixer. The founder. My whole identity reduced to scaffolding.

Recognition kept me in view, but it gutted me. People clapped for how much I could hold, but they never actually saw me. And after enough years of that, I couldn’t see myself either.

So I picked up my camera again. The same way I did when I was a kid. And it cracked something open.

That’s what Field Notes grew from — sitting with people, asking the questions that drop them past the surface, paying attention to what usually gets missed. The moments before they begin. The rituals no one names. The invisible labor that holds a life together.

What holds us has always been the same — the labor, the care, the noticing. That’s what the camera brought me back to. That’s what Field Notes is here to show.

Since I end every Field Note with a set of questions, I’ll leave you with these two:

What would it look like to measure progress by what actually holds?

What would it look like to live in a world where we didn’t just survive our jobs or careers, but poured ourselves into work — deep, meaningful fucking work — every single day?

Field Notes is how I came back to myself and how I hope we can come back to each other.

Until next time,

Lindsey

If you’ve been nodding along while reading and want to be part of the Field Year, you can join in through the GoFundMe. It’s a way to stand with the work that usually goes unseen.

Or if you have other ideas for collaboration or participation, don’t hesitate to connect.

ALL OF THIS.

I needed this today!!! My dose of Lindsey!